Oregon Cascades Volcanic Arc 400

The Oregon Cascades Volcanic Arc 400 is “a long-form mixed-terrain adventure cycling route spanning the vertical length of Oregon from Klamath Falls to Portland, predominantly tracing the western flank of the Cascadia Subduction Zone.” Ryan Francesconi

First, I want to direct your attention to Ryan’s write-up of the route here. Ryan is the route creator and has been working on it for over 7 years, and it's by no means an easy feat. This route has been on my radar since his write-up, and I’ve dreamt about riding it one day.

And I did.

The Route:

If I had to describe the route in one word, it would be “enthralling.”

In sum, venturing on the OCVA400 is like stepping into a terrain wonderland, taking cyclists on a journey along the mesmerizing Volcanic Arc-Zone. Imagine conquering mountain passes that keep your heart racing – a mix of challenging climbs and exhilarating descents that paint the landscape with excitement.

The trail, a canvas of pavement, gravel, and dirt roads, guides you through enchanting forests, occasionally throwing in a dash of loose dirt and sandy surprises. Each turn reveals a new layer of adventure as you pedal through challenging stretches. Lakes and reservoirs, like the stunning Giiwas Lake (Crater Lake), offer serene breaks in this symphony of landscapes.

Brace yourself for encounters with Oregon's natural marvels – the grandeur of the Cascades. Yet, the journey isn't untouched by the realities of wildfires, climate change, and internal struggle, adding a hint of unpredictability in the air. This isn't just a ride; it's a thrilling, demanding journey that calls for your adaptability, skills, and the endurance of an adventure seeker.

The riding window for The OCVA400 spans from mid-summer to early fall; the perfect window is harder to predict. Start too early, and you’ll run into snow on the passes and downed trees that haven’t been cleared up yet on the National Forest roads. Start too late and risk wildfires. Although riding it in the Fall with the foliage would be amazing, you miss out on the long summer days when the sunset is after 8 pm and risk riding in the rain. It's not too troublesome; it just defeats the goal of soaking up the vistas and views Oregon can offer rather than being soaked to the bone in Fall weather.

We chose to ride the OCVA400 at the end of July. That gave us plenty of time for the highest points of the route to be snow-free, trees cleared on main connectors, and get ample sun throughout.

We also decided to credit card the trip, riding from one motel to the other, point to point. The route deserves all the time you could give it, so if you can camp along the route, then I highly recommend that; there are plenty of unique camping spots all throughout. However, opting for the P2P meant we could go longer each day, have a lighter load, and start/end our day with the conveniences of the modern world: a warm shower, a generous meal, and a bed; that can be magical on such long rides. Albeit not sustainable on longer tours.

A note about the motels: the earlier you book, the better your chances are to break the route into manageable sections instead of succumbing to limited options, which might make your days shorter or longer based on your starting/ending point.

I’m not experienced in these sorts of trips (yet); however, like a moth to the flame, I felt a calling to do this for myself and to see my beautiful state from the place that defines it: The Volcanic Arc. Of course, I can't forget about the camaraderie and experiences you get from such rides, the highs & lows, the good & bad, and everything in between.

I was hooked.

The Crew:

Jack, Ira, Ryan, Tyler, Cody, and Trevor are part of the Rapha Cycle Club - Seattle Chapter. I first met Jack, Ira, and Ryan during the Rapha Triple Crown in 2019 in Winthrop, a weekend of big days in the saddle where we rode around the magical Methow Valley. We stayed in touch since, and in 2020, we ventured across Washington state, where we rode the Palouse to Cascades route, connecting it with the Iron Horse trail to Seattle. The ride traced a decommissioned train ballast bed traveling east to west over 4 days, passing through various topographies, mountain passes, endless wheat fields, and small towns.

Riding with them always meant going on an adventure, and I wouldn’t want to miss the chance to ride with them again. That chance came when we started talking about riding the OCVA400 in the summer of 2023, with the addition of Tyler, Cody, and Treavor, who are well-versed in these excursions.

The Gear:

July came fast, and I prepared my Breadwinner B-Road for the trip with new tires (Teravail Washburn 42s), a wider range cassette (XT 11-40), and an overhaul. In preparation for the massive climbs and heavy load, I decided to squeeze in as wide a range as possible on my setup, a hybrid of GRX and Ultegra.

I wanted to maintain the compact crankset (50x34) for the speed on the flats, which there isn’t a lot on this route, but that’s the setup I had. It worked great, pushing the limits on both ends of the gearing spectrum. The 34x40 gearing raised the ceiling, maximized my spin-ability up steep grades, and allowed me to climb in the saddle with a loaded bike. The rationale was that I wanted to spin to ease the climbing and avoid getting out of the saddle to not swing the bike around.

My choice of tires was the Teravail Washburns in 42mm, a semi-slick, fast-rolling tire, which was good when riding the route. However, in hindsight, I could’ve gone upwards of 45mm to accommodate the various terrains on this route. Sure, there’s a lot of pavement and graded gravel roads, and the 42mm tires performed as best as possible. However, had I gone with a slightly bigger volume, I would’ve had a better ride feel, given the bike's weight and the loose terrain earlier in the ride; you get a lot more in comfort and capability and don’t give up much.

All in all, I was happy with the setup for this trip. But as is the case always, I could’ve used more gears…

For the full bike setup + packing list, scroll to the bottom!

The Ride:

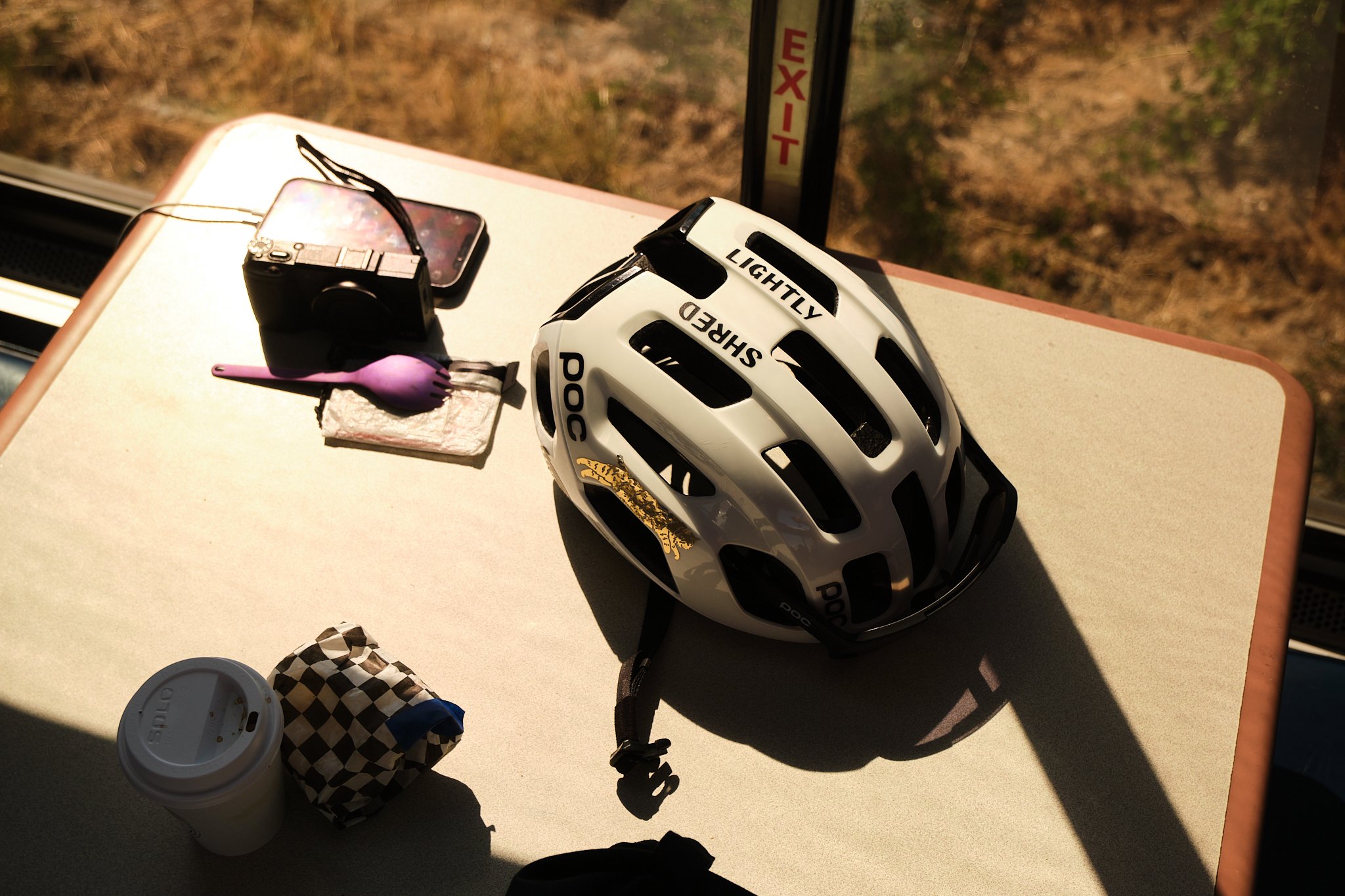

Day 0: Portland to Klamath Falls

Departure day.

The rest of the group lived in Seattle and started their long journey to Klamath Falls from there. The train to KF left at 9 am from Seattle. I jumped on that same train at 2 pm from Union Station in Portland, riding from home, with a fully loaded bike, a camera, and snacks (a burrito is a snack if you’re carboloading) for the long, long journey south across the Willamette Valley, and over the Cascades, intercepting some of the same roads we will cross the very next day.

Riding the train in the US is something you should experience, especially on the West Coast. Sure, it’s underdeveloped and (very) slow, and you’re at the mercy of Pacific Union and their schedule. Regardless, you get to see Oregon from a different angle.

About halfway through the train ride, just past Dexter, we saw a massive plume of smoke (Bedrock fire 2023) that seemed too close to the route, but upon further investigating that on the train, it appeared that the route was a few valleys to the east. Nonetheless, that fire affected the air quality on days 2 and 3.

We docked in Klamath Falls late at night, ready to lay our heads down for the long journey ahead.

Day 1: Klamath Falls to Diamond Lake | 79.5 mi, + 7,864 ft / -4,872 ft

First day, morale were high, but stomachs were empty, so first things first, breakfast.

We left the Mavericks Motel and headed to The Klamath Grill for breakfast. The route starts from downtown KF and goes straight up. The Old Fort Road heads up and over Plum Hills, heralding the steep pitches throughout the day. The road eventually turned to dirt halfway through, which felt like we were really “out there,” which we were! I felt confident about my setup up and over the first hill, although a bit heavy.

The fast descent down Old Fort Rd towards Algoma Rd unveiled the first view of the Cascades, with Giiwas Lake (Crater Lake) far north.

National Forest 9718 road runs over a towering mountain. It was a steep, ultra-punchy climb that started partly paved and quickly turned to dirt. That low gearing I put faith in came in handy. Along that climb, Jack and I were huffing and puffing our way to catch up with the rest of the group.

With every pedal stroke, we gained elevation, and slowly, M'laiksini Yaina (Mt. McLoughlin) rose across Klamath Lake. After so many years living in the PNW, these mountains still stop me in my tracks, and I find it hard to fathom the beauty, ruggedness, and wonders of the Cascades.

At last, the summit, or so I thought. On long rides, I like to leave my head unit on the map page, as I want to avoid looking at numbers. Full immersion? Maybe.

The NF9718 continues up further for a bit. The elevation (roughly 6000 ft), loose dirt, and sand made the climb tricky, foreshadowing the terrain about to come ahead. However, what’s the rush? Eventually, we reached the summit and started the 10-mile descent to Chiloquin for a quick refuel stop.

Powered by cheese, chips, a handful of olives, and the excitement of being out there, we marched towards the first nail in my Bonk-Coffin. For roughly 23 miles, I “rode” the sandiest sections on the route. Some sections were deep; others had fine sand that would kick into the air, leaving low-hanging dust clouds from riders ahead. I burnt a few matches, trying to stay upright.

Weaving between the cinder cones, we crossed the train tracks we were on yesterday, which eventually led us to U.S. 97 to the backroads towards the boundaries of Giiwas Lake (Crater Lake National Park)

The higher we climbed, the firmer the ground became and the thinner the air became, too. Over those dusty miles, I drank all three water bottles. The second nail in my bonk-coffin hammered in.

As I was descending into a mental valley of bonkiness, doubt, hurt, and all that comes with a tough ride, my spirit was lifted when we got to the Pinnacles, spires of hardened volcanic matter exposed due to thousands of years of erosion along a steep canyon.

Magical? It's just Oregon’s natural wonders!

The ride from the Pinnacles was paved, eventually leading us to the East Rim Drive. Things got dark at that point, and I got into my head. I could barely feel my extremities, my lungs gasping for oxygen, and my power, well, nonexistent. The view of the group fading down the road charged the disparity of catching up with them, but I eventually did.

As someone born with lung complexities, had had a collapsed lung before and lived with a weak raspatory system, I knew this would be an issue once we got to a higher elevation.

Just as I was diving deeper into the mental darkness and self-doubt, I heard one of the guys yell, “WATER!!” and I snapped out of it. By then, almost all of us were out of water. You’d think that water would be abundant next to one of the biggest lakes in Oregon. Well, it might be. It was just tough to get to.

The water trickled down a weeping wall, culminating in a shallow and faint creek. Small it was, but felt mightier than the Columbia River that day. Precious water, not even the biting mosquitoes, bothered me.

I filtered and filled all three bottles and hit the road again, trailing the rest of the group. I caught up with Trevor, and we climbed the East Rim Road until I couldn't pedal any further. The heat, exhaustion from the sandy section earlier, and elevation made it harder to pedal uphill.

I slowed down, my wahoo beeps *paused ride* on and off, my legs were numb, my fingers and lips tingled, and I felt foggy. I pulled off the road and laid down for 5 minutes on the side of the road.

I got mixed feelings about what I was going through at that point. On the one hand, I rode over Giiwas Lake (Crater Lake) with my buddies during the peak season. On the other hand, I felt disappointed and weak. My mind told me to quit because I had reached my limits, physically and mentally. It felt like my lungs were shutting down. I truly felt disappointed at the idea of quitting, raising the white flag, and just getting to the end of the day so I could hitch a ride back to the closest town.

The minutes passed, and I snapped out of it again “holy fuck, I’m riding my bike across Oregon.”

With renewed excitement, I jumped on the bike again and went over Dutton Ridge and down toward the base of Applegate Peak. The descent offered some solace, but the valley I was in was too deep to get out of completely.

There was pressure to make it to the Rim Village store to refuel since they closed early, or so we thought. Thus, some of us wanted to get there before they closed to score some food and drinks for the rest of us.

I was 5 miles/~1000ft away from the Rim Village, but it took me an hour to get there. The altitude sickness kicked in hard. I dragged my numb body up the steep hill, gasping for oxygen, with the occasional nerve shock down my legs and arms.

I was destroyed.

The Rim Village, at last. The looks on the guys' faces when they saw me were enough to confirm that I was in rough shape. Trevor grabbed my bike. I sat down and was fading in and out of reality.

Whenever I tried to eat or drink something, I felt like turning inside out. I simply couldn't force myself to eat. That was the most challenging moment for me as a cyclist. And I frankly just cracked. Tears were dripping down my face, but I could barely tell.

It turns out that the Rim Village store had extended hours, and the guys were patient enough for me to catch my breath as if that was possible anyway. I felt sick and lightheaded and had a weird shooting pain in my chest that made me concerned. As well as trying not to puke my guts out.

Yeah, it was rough.

The guys and I made the rational choice to find a way to shuttle me to Diamond Lake, where we already booked rooms for the night. Although I was trying to get back on my bike, I could barely keep my balance and had to put what was left of my pride aside and find a ride down. The last thing I wanted was to get into some accident or ruin the ride for the rest of the guys with my stubbornness.

Luckily, Jack found a family that was headed back to their cabin in Diamond Lake and was willing to give me a lift. I felt bad for them since I was covered in salt, sweat, and dirt and definitely smelled terrible. But I was also grateful because they saved my butt.

I got to the lodge, showered, put my bike together, and forced myself to eat a few sandwiches. Then I just waited for the guys to roll in. I sat by the road and waited to see 6 headlights rolling down the road towards the lodge.

And there they were! With pizza boxes on their handlebars, too!

With that, the ride's first, the first day behind us, and a long night of rest ahead. I was still unsure of how I would feel the following day. But a warm shower, a full night of sleep, and a few cups of coffee in the morning beat any over-the-counter remedies money can buy. The lower elevation (5300ft) helped a bit.

What a day.

Day 2: Diamond Lake to McKenzie Bridge | 127.1 mi, + 7,245 ft / -11,194 ft

Day two.

6 am, my alarm went off. I felt strange, strangely okay! What happened to the commotion of yesterday? What happened to almost passing out and barely balancing myself? It was as if nothing had happened. Don't get me wrong, I felt tired, but not proportioned to the suffering I went through the day before.

The human body is amazing. And so is coffee.

I packed my bike and met the guys at the lodge for our second breakfast on the journey. It was great seeing everyone prepared for another epic day across the Cascades. Fed and caffeinated, we rolled out of Diamond Lake North.

The day started with a fast descent toward NF430. The red dirt was a sign that we were closer to Central Oregon. Riding through the closed canopy of giant Ponderosa, with their rock-like bark, is a rite of passage for any cyclist in Oregon. You have to experience it.

The route profile of day two had more down than up. However, the climbs were long and steep in some sections. You must pay the toll somehow. We crossed the North Umpqua River and started the first long climb of the day, FR700.

The terrain got rockier and less sandy by the mile. The group organically separated a few miles up the climb; some were fast up the hill. I got into the granny gear and spun up.

This climb makes you want to keep moving because the mosquitoes will swarm you if you don’t. However, it’s also important to balance that with stopping to look behind you briefly. Some of the best scenes might be in the background.

The calmness of the high desert is unmatched.

At the summit, we regrouped before the long descent to Oakridge, 44 miles. The mixed terrain descent, switchbacks, and vistas made this the best day on the trip. The energy was unmatched, everyone felt good, and the weather was great.

Along the descent, we transitioned from high desert to lush forest, marked by the change in flora, dirt, and abundance of water around. Perhaps the “Big Swamp Rd’ was an indication, too!

Crossing boundaries.

By midday, we reached Hills Creek Resiviour, which sits above Oakridge, the second biggest town on the route. By then, the heat had settled in, and smoke from the Bedrock fire was noticeable.

We reconvened at the local grocery store to refuel on the good stuff: pasta salad, jojos, cheese sticks, pickles, water, and lots of ice. I filled the back of my jersey with ice to lower my temperature. During the pitstop, a couple from Germany rolled over on their tandem bike and chatted with us about the road conditions and such. They were on their way south, towards Latin America. Although they were amused by the speed we were riding across the state, we admired their long journey across the continent.

Going it slow is the way to go sometimes.

Loaded on carbs, water, ice, and everything nice, we rolled out of Oakridge, seeking shade on High Prarie Rd, the climb out of Oakridge. Although most of the climb was shaded, we got to a clear-cut section that revealed the giant plume of smoke from the Bedrock fire just west of us. Within 48 hours, the fire quadrupled, consuming an extensive section of the steep valley where it started.

Eventually, the pavement ended, and the road turned into FR1928. Getting back into the forest improved the air quality ever so slightly. This section ended with another fast downhill to a fork in the road, turn left and go hard with more gravel, or turn right towards manageable and smooth roads? We all voted for the latter, and it was a great choice as Aufderheide Drive was one of the best sections on the route.

It was quiet and serene and didn't push the envelope on a long day in the saddle. Although the last summit was very steep, what came after was worth the effort; A fast, snappy descent on a perfect pavement in the middle of the state with no cars around.

Along the downhill, Jack recalled a classic handle-actuated water pump at Frissell Crossing Campground just around the corner. Our bottles filled with ice-cold water, we continued our way towards McKenzie Bridge. The smoke, albeit irritating the lungs, certainly added much character to the afternoon sun. The sun casts golden light, illuminating the road ahead.

When we reached Cougar Reservoir, the light had changed as the sun had sunk behind the smoke. Pondering the sunset was the 3rd person we saw after Oakridge; we had the backroads all to ourselves. He clearly did not expect to see a group of cyclists rolling down the road on a Monday evening, especially not on those backroads.

We rode around the reservoir and descended under dramatic smoke clouds that split the skies in half, and once we crossed the historic McKenzie Bridge, day two came to an end. Another piece of this odyssey completed.

The rush to catch the only restaurant in the area was on as soon as we arrived. Although the menu was extensive, I was drawn to the salad bar as a constant stream of all the salty stuff I could pile in a bowl, slathered with vinaigrette and cheese. An abomination on a typical day, but it seemed necessary to pack as much salt as possible on top of the main course.

Eat like it is your job!

The longest day had yet to come.

Day 3: Mckenzie Bridge to Portland | 168.2 mi, + 9,250 ft / -10,255 ft

Day three. The long ride back home.

Overnight, the wind brought more smoke into the valley, which made the start of that day quite the adventure. On top of that, the only restaurant in town opened after our intended early departure, and we were left with only one option: the gas station next to it.

I should’ve mentioned this earlier, but I recalled that I had an “emergency” can of cumin and parsley chickpeas from Trader Joe's as a contingency plan in case I needed it, and I did that morning. Gas station food is generally a go-to on these big rides, but starting so early meant we were bound to what was in the fridge from the days before.

“Fed” and ready for the longest day ahead.

The ride out of McKenzie Bridge follows a long but gradual climb up towards Old Santim Pass. We had two options to climb out of the valley: ride on the road and save time or ride on the single-track alongside the McKenzie River. As much as I would've loved to ride the trail, the group decided to take the road. This means I’ll have to ride it on the next run on the OCVA400!

The smoke was getting to me; as you recall, I grew up with lung complications, so I wasn't too stoked about the air quality and took my time climbing up. The smoke did add to the magical feel of the area; after all, wildfires are essential to this part of the state, although not at the rate it has been lighting up the past decade.

The natural cycle took its course, and we witnessed it.

Eventually, we connected with Santim Wagon Road, passing through Fish Lake. Riding over pine needle-covered wagon trails, we continued up the pass. The smoke got thicker the higher we climbed; however, once we crossed the Santiam highway, it was an instant transition from smoky to blue skies dotted with cumulus clouds. I can't stress the “instant transition” part enough. One end of the highway was smoky, while the other was not. I thought the smoke got to my head. I was bewildered by that sight!

With the lava lands behind us, we continued north to Detroit Lake.

From this point onwards, the forest roads looked similar to what I usually see west of the Cascades: old forgotten roads, reclaimed by nature, that turned what once might been a smooth pavement/gravel road into glorious mossy doubletracks amongst old-growth.

Nature prevails, if we allow it.

And just like that, we reached the second to last climb of the day. You get accustomed to the multi-surfaced, prolonged twisty drops at this point of the ride. Light shined through the dense evergreen canopies—the continuous compression and expansion of the forest around you. The rush you get from the speed and the sudden opening up of the forest above you, with views of the cascading mountains on the horizon, a split of a second is all you get. Still, it’s somehow enough to make an everlasting impression in your mind.

This gets me every time. The poetic aspect of these rides through the in-betweens is probably why I still ride my bike.

At last, Detroit Lake.

I was orbiting planet Bonk (as coined by Garret Holbrook). The long day showed the cracks I’ve accumulated over the past +200 miles, with over 28K feet of elevation under my heels. I slowed down and went into limp mode. However, on this part of the ride, my north star was a Mexican food truck in town.

The prospect of a few burritos and tacos in my future certainly lifted my spirit.

We refueled, restocked, and hit the road for one last climb, Britenbush Road to NF6350.

Keeping the group together for the last climb, we slogged up the ridge. You could see the extent of the damage that the fires caused over the years, most notably the Detroit Lake that ravaged the town and burned many acres. Towards the middle of the climb, you get a sense of the damage the Britenbush fire caused to the area. Giant trees, dead, yet standing tall, towering above the new growth below them.

Near the summit, I turned around to look at central Oregon one last time before the ride down towards the Clackamas River. I bid farewell to Seekseekqua (Mt.Jefferson) and its mystical forest. I tucked in for the last major descent on the route.

Until that point of the route, almost all the miles we covered were new to me. Although I knew where I was, I didn’t have that spatial recognition as you would with rides you’ve done before. However, as soon as we crossed the Clackamas River, I knew instantly where we were, and just like that, the ride transitioned from the unknown to the known.

Crossing the boundaries into the known signified the end of the ride, in some sense.

The Clackamas highway follows the river downstream, through the canyon it carved into the foothills of Wy'east (Mt.Hood) over millennia. The gentle downslope took the edge of the howling headwind rushing up the valley. However, as evening approached, the wind eventually turned to a breeze.

Closer to Estacada, we got off the highway and onto a multi-use path road. East Farady Road meanders along the North Fork Reservoir, eventually connected with the Clackamas highway again just outside Estacada.

I was 25 miles from home by the time we reached Estacada and, with that, said goodbye to the group as they continued to their last accommodation stop in Sandy. What a journey that was with those guys; simply phenomenal.

I decided not to rush the last 25 miles and instead took it as an opportunity to reflect on the adventure I had just done. Riding across the state might be an accomplishment, but it is more than that. These adventures are not designed or built around achieving statistical significance to share on cycling social media. It is an opportunity to soak in the elements of a place that embodies the meaning of “natural wonders.”

I reflected on the reality that I had just ridden the entire length of Oregon, crossed natural boundaries, bonked beyond my imagination, flew underneath canopy roads, and shared 3 days in the saddle with great people. I also thought about rewarding myself with a Popeyes chicken sandwich, and there just happens to be a branch a few miles away from home. Fate, is that you?

I rolled down the drive-through (Portland drive-throughs are not car-exclusive), grabbed my reward, and sat on the sidewalk in disbelief that that trip had happened. A chance encounter with Ryan Fransisconi (creator of the route) brought a fitting closure to this memorable odyssey.

Thanks for the Kombucha and Mochi ice cream, Ryan, and for sharing this fantastic route with us!

Until next time, I am steeped in the memories of this adventure and look forward to the next one.

Photo by Ryan Fransisconi

Bike Setup + Packing List:

-

Breadwinner B-Road, Mixed GRX & Ultegra groupset, 50-34x11-40, 42mm Tervail Washburns, Hippack (carrying tools, money, snacks, dynaplugs, super glue, emergency blanket) Revelate Designs frame bag, Apidura 14L Saddle Bag, Wahoo Roam, SPZLD Flux 850 Headlight, Cygolite rear light.

-

Description text 2 kits (interchanged, one worn, one packed)

1 vest + rain jacket (it's Oregon; anything can and will happen!)

1 technical shirt (for on and off bike)

Sunglasses

1 pair of shorts

1 packable puffy jacket

2 pairs of socks

2 underwears

1 cycling cap

ID, CC, and $40 cash (just in case)

Water filter

3 water bottles

A small bag of toiletries

Portable charger and cables

1 camera + lens + 2 SD cards

Instant Coava coffee (slaps hard!)

Titanium cup (saving weight)

1 can of Cumin Chickpeas (emergency food? maybe) + Bike snacks + 1 emergency mustard pack + a bunch of Salt sticks

Headlamp

1 shifter cable (backup)

Small thing of chain lube + rag

1 Mussette goes here